Originally posted August 19, 2019 on interiordesign.net

Leslie Larson, a Boston-based lighting designer and wood sculptor, began his 1964 disquisition “Lighting and its Design” with the observations that there were few well-designed lighting fixtures commercially available in America, and that architects too often neglected lighting design as an integral aspect of building. Larson himself designed both lighting systems and fixtures, and in his book, he makes a case for the importance of good lighting, and not incidentally, a good lighting consultant.

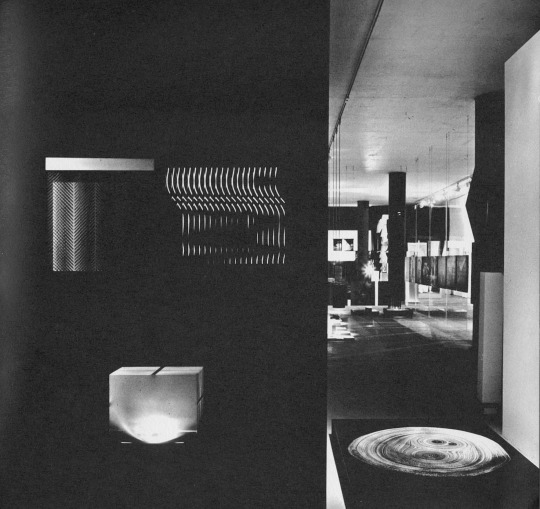

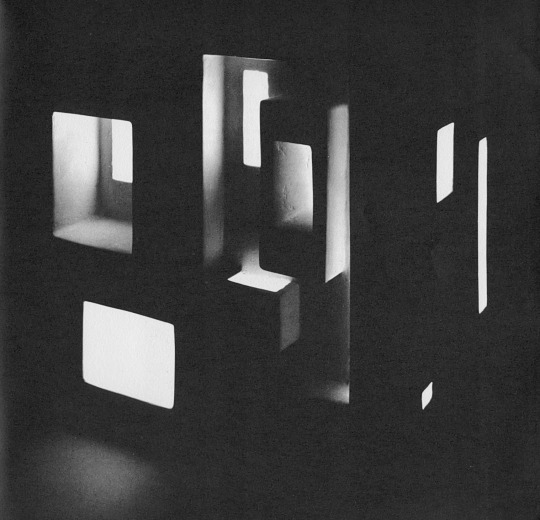

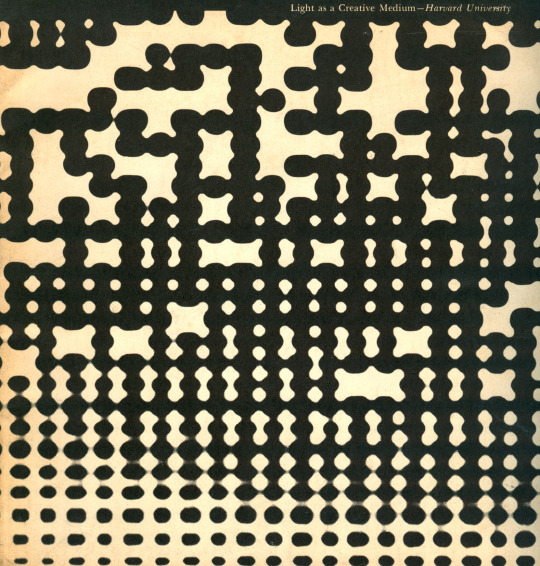

On a fundamental level, Larson points out that without light, form and space are not visible, and that the influence of light on the culture and psychology of man is too great for it to be treated mechanically. In short, lighting needs to be considered as a design problem, not an engineering one, and needs to be treated with specificity and with an awareness of both physiological and psychological needs. Beyond enabling the eye to function freely, a good lighting solution enlivens a space and addresses needs for excitement and repose, variety and even drama. Shadow and darkness, as well as natural and artificial light sources, are key elements for Larson–that the illustrations are all in black and white emphasizes this.

Larson provides numerous examples of buildings with well-handled lighting. These range from churches and cathedrals to auditoriums and offices–from the sacred to the profane. Ronchamp and the Guggenheim are singled out, neither surprisingly. Six projects caught my attention as good illustrations of Larson’s argument, and beautifully lit spaces:

1. The Vasterport Church in Vallingby, Sweden, architect Carl Nyren. Natural light coming from on high creates a spiritual aura, while the wall brackets add to the drama.

2. Dome over the Palazzo dello Sport in Rome, architect Paolo Nervi. Light and shadow define Nervi’s masterwork. By day, the brilliantly lit center recess is the focal point set against the softly lit radiating ribs. At night, the dark-lit pattern is reversed.

3. Interior of the Chase Manhattan Bank in Great Neck, New York, The Architects Collaborative. A humble space that is nonetheless crisply delineated by light and shade.

4. The Olivetti showroom, NYC, BBPR architects. The contours and textures of the sand relief mural by Constantino Nivola pick up light and cast shadows; the whole is vividly outlined by cushions of light. Note also the Venini hanging fixtures, which really beg to be seen in color.

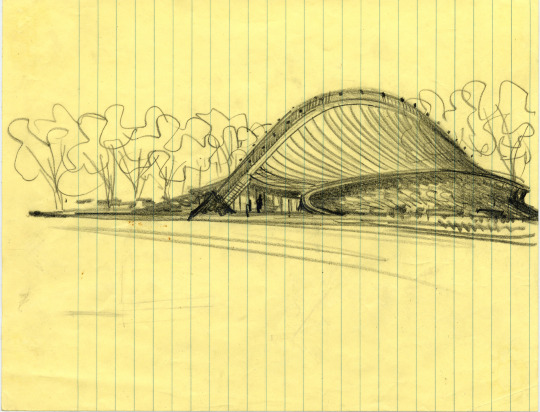

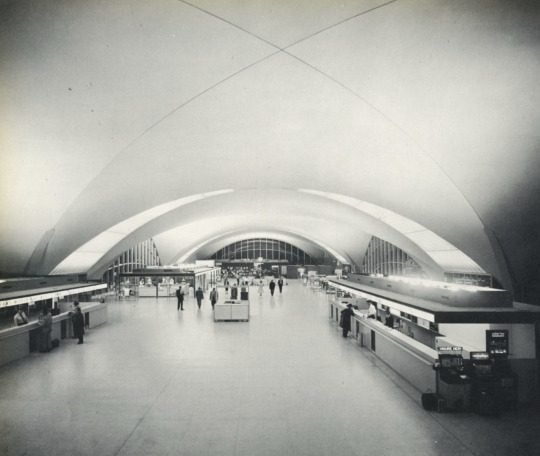

5. The St. Louis Air Terminal: Hellmuth, Yamasaki, and Leinweber, architects. Skylights at the junction points of the interlocking vaults provide natural light, while artificial lighting is placed above eye level. Light is projected upward at the surface of the vaulting, which becomes luminous in gradations.

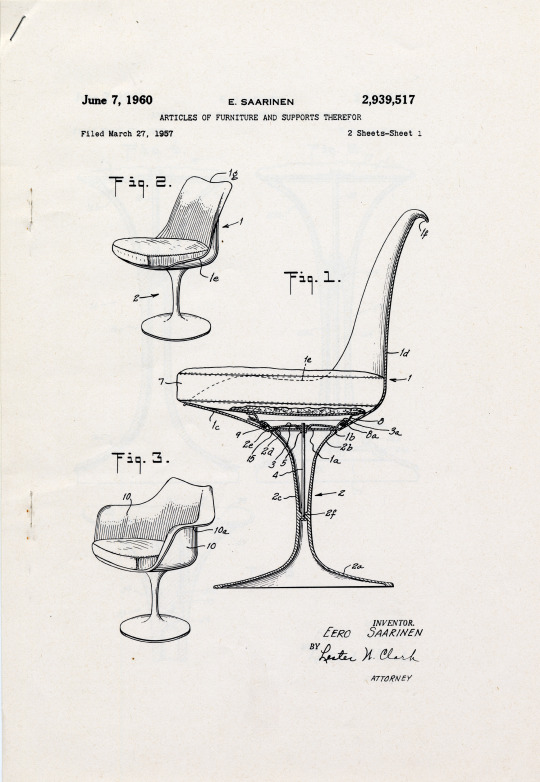

6. Kresge Chapel, MIT: Eero Saarinen, architect, with Stanley McCandless, lighting consultant. An American Ronchamp, perhaps. Poetically lit with direct light from above, which filters downward via Harry Bertoia’s shimmering metal screen.