Originally posted May 13, 2010 on interiordesign.net

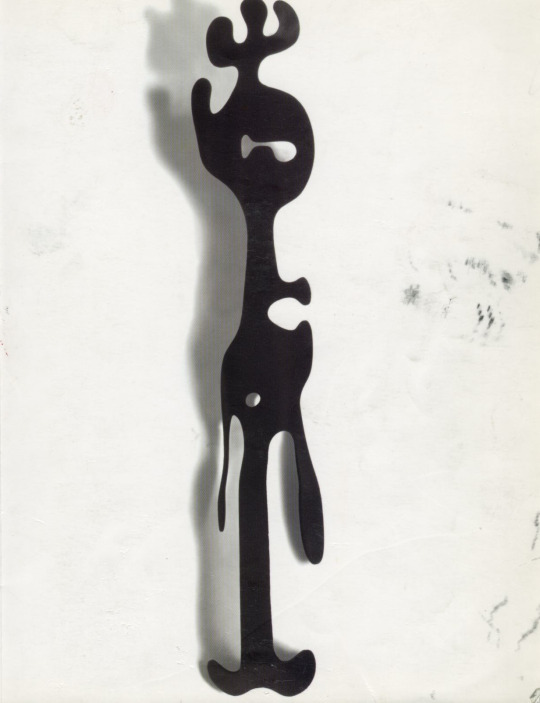

Before the Italian sale, before the Louis Kahn house, before the $500,000 Noguchi coffee table, and before branded luxury, there was the Treadway/Toomey Eames auction held on May 23, 1999. For Richard Wright, who curated and produced the auction, this represented a point of departure from Treadway, where he had worked for a number of years, and an early collaboration with Julie Thoma Wright, his wife and business partner-to-be. For the market, the auction represented a succession of firsts: first all-Eames sale; first Ray Eames splint sculpture to be offered for sale; and first catalog without a logo on the cover, with the title running across two pages, and with photos bleeding across pages. Soon after the Eames sale, Richard founded Wright, his eponymous auction house, which has since become a force in the modern design and art markets, elevating Richard to first-tier status as a market-maker and connoisseur. In the spring of 1999, however, Richard still worked with Treadway, and his future plans were still on the drawing board.

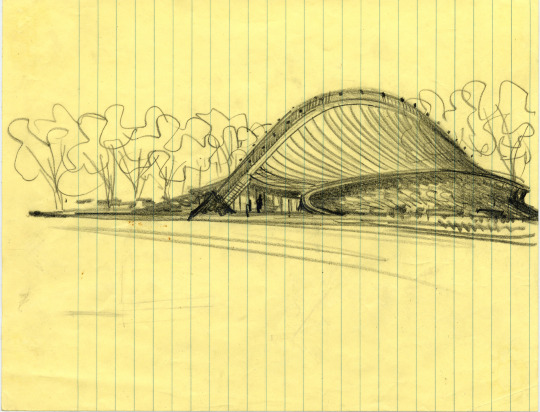

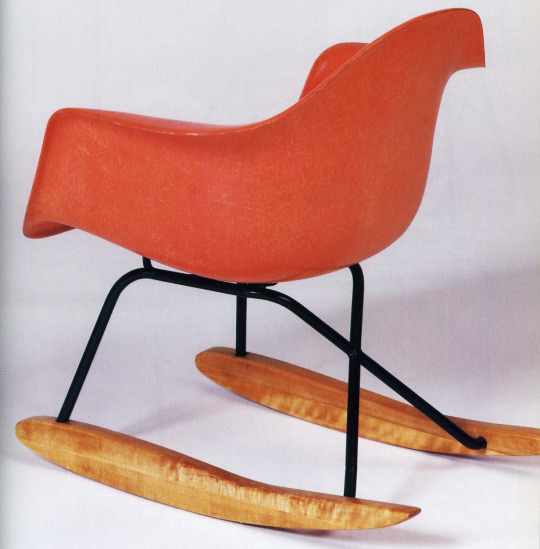

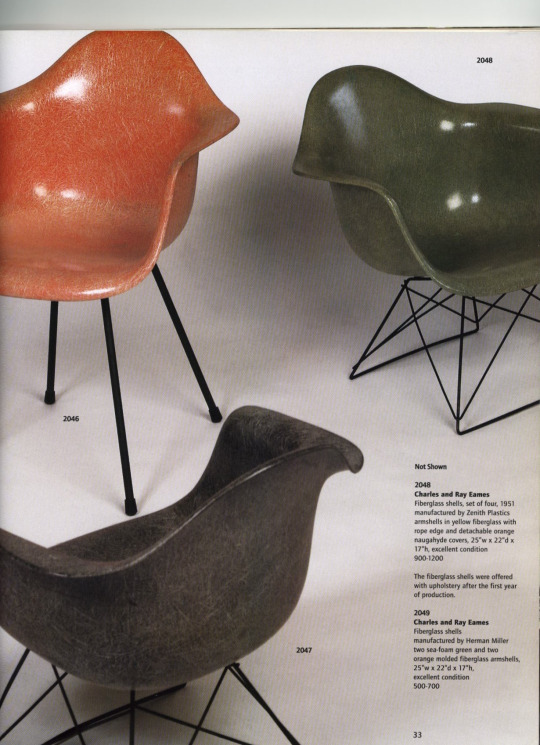

The Eames auction would give Richard a chance to show what he could do, both for himself and for the design world. Over a period of two years, Richard assembled a collection of Eames material, reflecting his own interest and belief in the work of Charles and Ray. Highlights included the well-edited Breeze-Stewart collection; a trove of Eamesiana from an estate sale of a distant Eames relative that Richard said he was proud to handle; and the fluid Ray Eames splint sculpture, important for both aesthetic and historical reasons—it helped put Ray’s contribution back into the equation. Early designs, production variations, and prototypes were featured. The auction was pitched to collectors, and timed to coincide with a major Eames retrospective opening in Washington, D.C.

At the time, assembling this material for a dedicated sale was a bold step, but no more so than re-thinking what an auction catalog could look like. Working with Julie, hiring a graphic designer out of pocket, and micro-managing practically everything, Richard wound up pushing the boundaries of auction catalog design. The finished product would become a template for his later, more polished efforts, which, in turn, would provoke change in catalog design at the larger auction houses.Wright’s timing, as it would often be, was impeccable. Collector interest in the Eames’ work ran high, supported by renewed attention from shelter magazines. Recent reproductions from Modernica and Design Within Reach added publicity, without yet cluttering the field. The tech-fueled economy was booming.Eames collectors were—and probably still are—an obsessive and determined bunch. In the late 90’s, we (guilty) shared a sense of discovery, not just of the Eames oeuvre but of a body of exuberant and innovative work that was American mid-century design. Still, the greatest enthusiasm was reserved for things Eames. People who otherwise, and later, would champion Line Vautrin, Paul Evans, and Ado Chale, spent inordinate amounts of time rhapsodizing about zinc screws, rope braids, screw-in feet, and early Evans labels, and speaking in shorthand—DCW, ESU, 670 ottoman in rosewood with down fill. Technical and chronological details mattered, a lot.

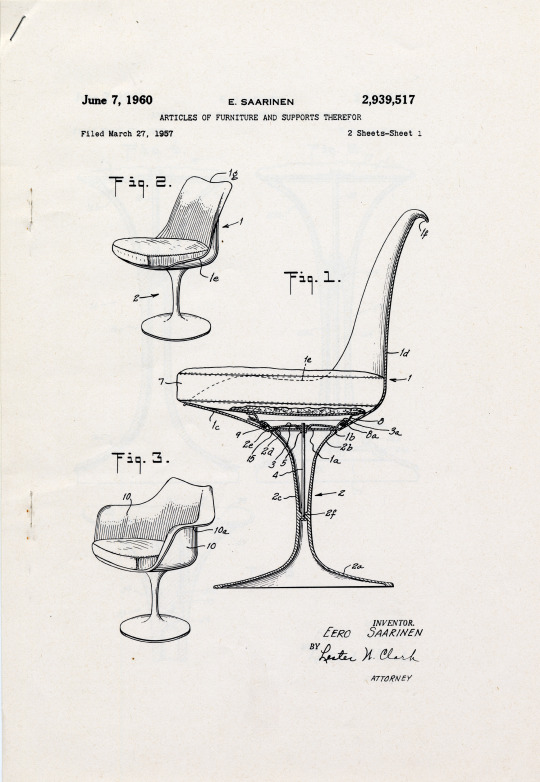

The sale whipped this crowd into a frenzy. The results surprised even Richard. One hundred percent of the lots sold, with many achieving stunning prices—a child’s chair brought $15,000 (try repeating that now), a lot of letters from Charles to the Saarinens brought $5,000, and a slunk skin plywood chair in pristine condition brought $35,000. Nothing, however, topped the whopping $130,000 commanded by the splint sculpture, on an estimate of $25,000-35,000.

The success of the Eames auction solidified Richard’s position in the design community. More, it gave him the courage and the means to start his own business. Looking back at the catalog and the sale, Richard is amazed—amazed perhaps by his audacity of concept and design, or perhaps by his subsequent run of success. The ripples from the Eames sale would help transform the market for mid-century design, as other auction houses scrambled to gain a share of this increasingly lucrative sector. Last month Richard revisited this idea with his second all-Eames auction. Unfortunately, the centerpiece lot—the Neuhart archive of Eames ephemera—estimated at $150,000-$200,000—was withdrawn due to a contest over title. As Richard noted, it’s hard to go home again.