Originally posted June 11, 2009 on interiordesign.net

Let’s start with the good news: “African and Oceanic Art from the Barbier-Mueller Museum, Geneva: A Legacy of Collecting,” running through September 27 at the Met, is a show well worth seeing. The exhibition features 36 works—all masterpieces—from one of the world’s great private art collections. Begun by Josef Mueller (1887-1974) in the 1920’s, and continued by his son-in-law Jean-Paul Barbier-Mueller, the collection was placed on permanent display in 1977. The works on view range across a wide swath of Africa and the South Pacific, and they brilliantly demonstrate the virtuosity and formal inventiveness of individual creative talents.

Now for the not-so-good news: from the title to the installation to the catalog photography, the exhibition raises issues, or at least fails to resolve concerns, which make it difficult to absorb the magnitude of the works presented. Putting “A Legacy of Collecting” in the title forces us to consider the ramifications of collecting at a moment when ethnographic art is coming under the same scrutiny as the art of antiquity. The legacy of collecting ethnographic art is increasingly being discussed as a legacy of inappropriate or questionable acquisition, if not outright looting of cultural patrimony.

While this is a complex issue, particularly in legal nuance—the UNESCO Convention of 1970 only went into effect in Switzerland in 2005, and is not retroactive—it is also a concrete and politically charged issue. A cursory internet search of “Barbier-Mueller Museum” reveals a dialogue of protest, aimed directly at the Barbier-Mueller holdings of excavated terracotta figures, but also at the depletion of African cultural artifacts in general. One such broadside, written by Dr. Kwame Opoku, spells out the damage caused by alienating tribal objects from the fabric of context, and makes a reasoned and measured claim on our collective sense of fairness.

The installation of the Barbier-Mueller pieces at the Met does little to dispel the echoes of pleas such as these. The monumental, neoclassical space which forms the backdrop, tied to the Rockefeller name, only underscores the colonial power inequities at the center of contention. The installation itself, with the objects inaccessible and captured behind glass or in glass boxes on pedestals, along with the catalog photographs of isolated objects set against solid but empty backgrounds, serve Western eyes and sensibilities at the expense of African and Oceanic notions of context and meaning.

In a review for the New York Times last week, Holland Cotter argued that the Barbier-Mueller exhibition puts notions of “primitive” to rest and tells us that African art is not a fixed set of forms repeated verbatim, but an art of specificity and individuality. While this may be so, the same can be said of the 1996 Guggenheim exhibition “Africa: The Art of a Continent,” which made these points on a much larger scale—some 500 objects—and a more conducive stage (Frank Lloyd Wright’s idiosyncratic and expressive building).

Perhaps it is time for museums to move beyond polemics on these two points—primitivism and traditional invariance—and to more fully and directly engage the pressing topical matters of context and repatriation. As with green design, this genie is not going back in the bottle, and museums that ignore or under-represent the African perspective in tribal arts exhibitions will appear increasingly retrograde and arrogant. Go to the exhibition at the Met to see these masterpieces of art, but recognize that the Met is something of a museum of Western museology.

If you are inspired and engaged by ethnographic art, as I was at the Guggenheim show, I recommend reading any catalog published by the Museum for African Art, and patronizing that museum when it re-opens on 5th Avenue and 110th Street.

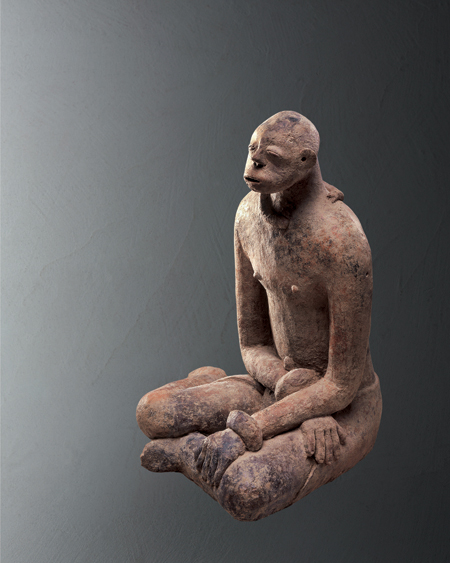

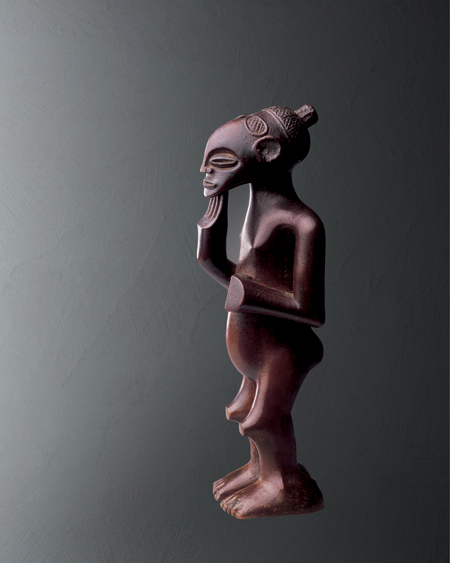

From top: Power figure, Nkisi, Democratic Republic of Congo, 18th-19th century, courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; mask, Torres Strait, Saibai Island, 19th century, courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Josef Mueller, circa 1967; kneeling male figure, Mali, 14th-16th century, courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; male figure, Easter Island, early 19th century; female figure, northern Angola, Shinji, 19th century, courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Barbier-Mueller Museum Canoe prow ornament, Solomon Islands, in case, photo by Larry Weinberg; Poro female figure, Cote d’Ivoire, Senufo, 19th century, courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; funerary figure, New Ireland, 19th century, courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.