Originally posted October 22, 2009 on interiordesign.net

When Gordon Drake died while skiing at age 35 in 1952, he accidentally ended an architectural career that was as meteoric as it was brief. In seven years, he completed a scant dozen or so buildings, but his first two won national recognition in architectural competitions, and his reputation was such that his buildings, sketches, and writings influenced the postwar built environment, and inspired a book, “The California Houses of Gordon Drake,” published in 1956.

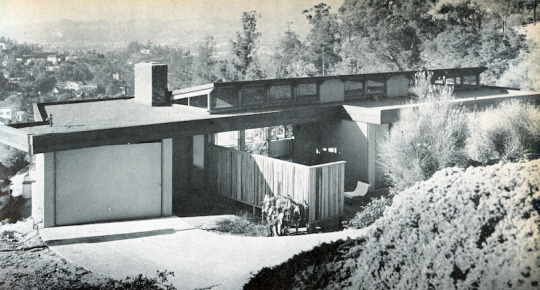

Born in Texas, Drake served in the Marines during WWII and moved to the West Coast when discharged. More than anything else, Drake was a California designer, working out his ideas with respect to local climate, topography, lifestyle, and mindset. As he noted at the beginning of his career, “the dominant factor in the development of California’s domestic architecture has been the…lack of a stifling formal tradition. The resulting freedom of thought has given the architect an untrammeled concept that does not exist in other parts of the country.” Drake’s contribution to this concept was a vision of the small house, artfully sited in nature, well suited to indoor-outdoor living, and affordable.

Like many mid-century designers, Drake’s first project was done for himself, and at low cost. Completed in 1946, the Drake house in Los Angeles won first Prize from Progressive Architecture in a competition aimed at raising contemporary standards for residential living. An editor noted, “Seldom does one see work in which structure, site, and clients’ needs merge so completely in the process of design.” Recognition was also given to Drake’s next project, the Spillman House (also in LA), which won second prize in House and Garden’s 1947 Award in Architecture.

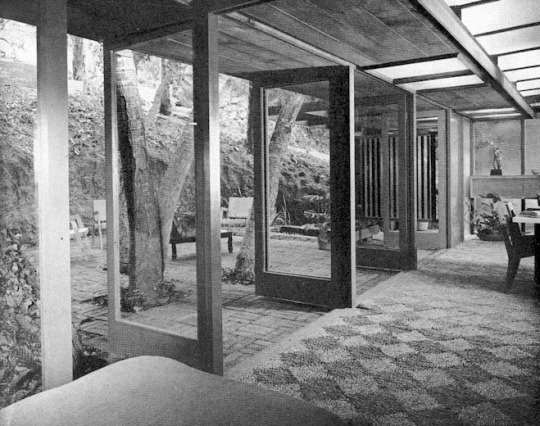

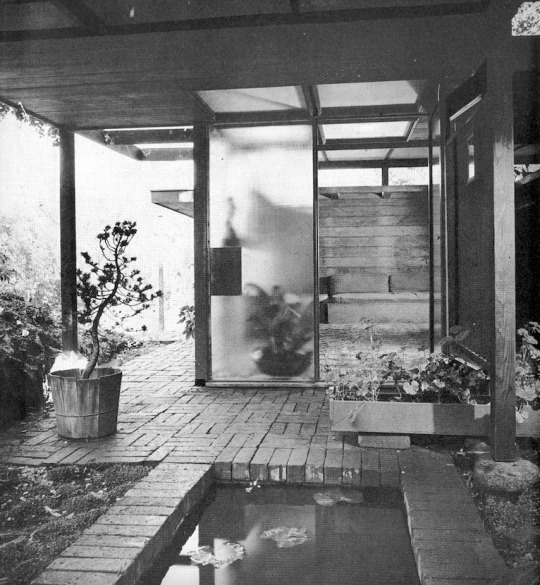

Drake’s first houses served as a template for his subsequent work in terms of the liberal use of timber and plywood, in the centrality of light as a design element, in the integration of natural beauty with structure, and in the simple, modular construction methods. Wood was prevalent in California, and inexpensive. Drake favored rough-hewn boards on the outside for form and texture, set off against the “magnificent sophistication of waxed plywood on the interior.” Natural light was brought into the house through clerestories, glass gable ends, translucent screens, and glass walls. Both natural and artificial light were modulated to create moods and meet use requirements.

All of Drake’s efforts were intended to bring a decent quality of living to the general public, to make good design in architecture affordable. As Walter Doty noted of Drake, “He felt that architecture was without meaning until it was used. The publication of a prize-wining house meant very little unless it brought about the designing of thousands of houses…” Drake himself sought an attitude of humility in himself and his building, stating “Buildings are judged by whether or not the people who live in them are happy or unhappy.”

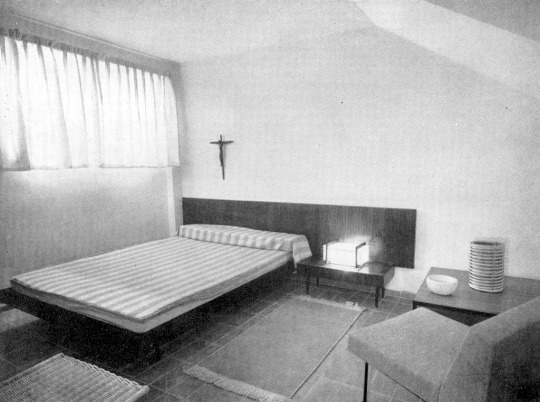

Looking at Drake’s work, one is struck by its restrained elegance, by its almost Asian sparseness and simplicity, by the beauty of its site, and by the seamless integration of indoor and outdoor spaces. Indeed, his work is its most impressive and exceptional at the liminal—the boundary—between indoor and outdoor, the precise point at which California architects embraced their zeitgeist. Most of the photos in the book stress this—doors or screens are shown open, so that outside space flows in, and vice versa. And strictly interior shots are pedestrian compared to the beauty and originality of shots involving outdoor areas—shots of houses set in their surroundings, of adjacent terraces, patios, and gardens, of outdoor areas looking inside, or inside spaces looking out.

Drake’s work illustrates the new way of living developing in California after WWII. His career helped demonstrate the feasibility and even practicality of low-cost, high-quality design in domestic architecture, and expanded the sense of visual possibility in regard to indoor-outdoor living.