Originally posted September 17, 2009 on interiordesign.net

When you think of Spain, mid-century design is not the first thing that comes to mind…or the second…or third. In fact, you would be hard-pressed to name a single Spanish designer or architect working after Gaudi, except for Jose Luis Sert, who left Spain for America in 1938. I’m not sure why this is, but two possibilities suggest themselves.

First, Spanish modernism simply languished after WWII. Second, post-war Spanish modernism is out there to be rediscovered. Given the virtual absence of Spanish sources in the major design yearbooks of the mid-century—Arredimento Moderno, Studio Yearbook, New Furniture—and the presence of Latin American architects and designers such as Niemeyer, Tenreiro, and Rodrigues—it is tempting to conclude that less modernist work was produced in the mid-century in Spain than elsewhere, and what there was flew under the radar to begin with an exhibition held at The Met a few years ago, “Barcelona and Modernity: from Gaudi to Dali,” tracked Spanish art, architecture, and design in the first three decades of the twentieth century, from the glory of Gaudi to the reaction against the perceived excesses of Art Nouveau.

By the 1920’s this reaction took two forms: a revival of interest in tradition in architecture and handicraft, and the emergence of a school of minimalist rationalism that became the Spanish arm of CIAM and that culminated in the Barcelona Exhibition of 1929, with the famous Mies Pavilion and the Barcelona chair. After 1930, it seems that much of the story simply remains to be told. The strong impulses in Spain toward tradition and minimalism, coupled with Catholicism and fascism, may not have been conducive to the exuberant brand of mid-century modernism of Eames, Molina, and Finn Juhl, but they were not necessarily inimical either. Too, the Spanish mission style, transplanted to California, was one of the progenitors of 20th-century design. Sooner or later, we would expect to find Spanish modern design, whether pan-European or regional and idiomatic. The question is, where?

One answer is in the pages of “Arquitectura Interior,” a yearbook of design published in Madrid and edited by the architect Carlos Flores. I have four volumes in my library, 1959 and 1962-4. The 1959 volume provides something of a survey of the European and American modernism of the moment, and while it includes some indigenous Spanish design, the gist is that of spade work—a primer on the New Look for a constituency just being exposed to it.

By 1962, however, the task of defining and promoting Spanish modern design has begun in earnest. The introduction, roughly translated, predicts that contemporary Spanish living environments can soon be furnished with Spanish design exclusively.

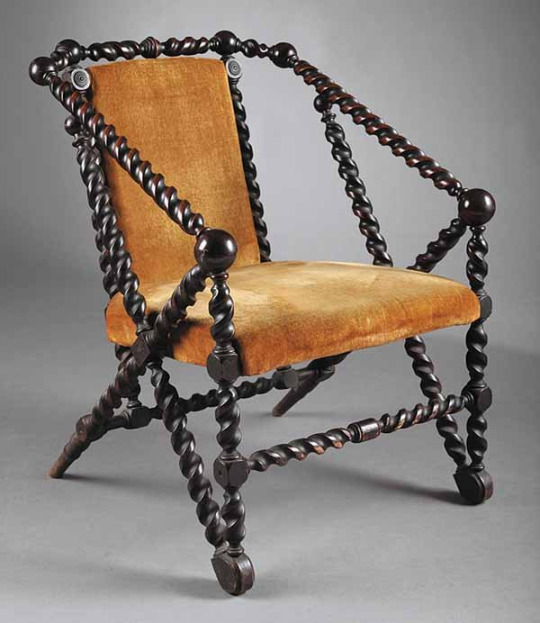

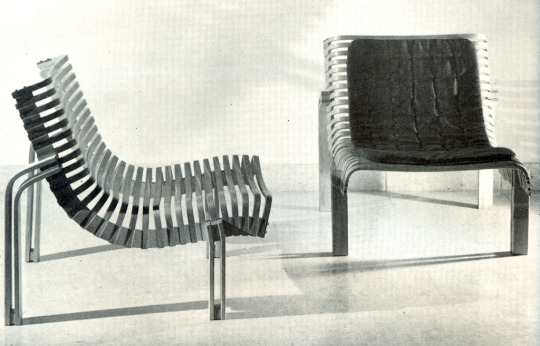

While this confirms the supposition that there was little in the way of Spanish modern design through much of the 1950’s, the 1962 issue introduces us to a host of Spanish designers now plying the modern idiom, and doing so with confidence, inventiveness, and verve. I’ve singled out a cantilevered steel chair by Fernando Ramon, referencing Mies, as a point of departure; a table by Antonio de Moragas that channels mission in its solid simplicity, with a nod to the mid century in its flexibility—the top slides to any position—and demountability; an auditorium chair by Miguel Fisac with a nice posture and sculptural presence; a rakish three-legged plywood chair by Jose Dodero recalling Wegner, Prestini, and Tenreiro; a nice constructivist chair by Julio Bravo, et al; and a fluid lounge chair by Equipo 50 revealing its skeleton of wooden slats.

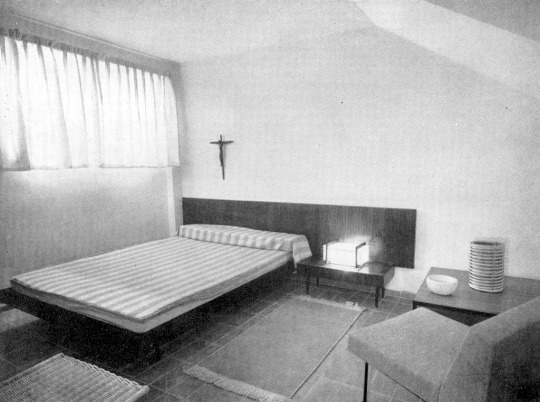

As for interior design, I was drawn to the clean, Spartan spaces that recalled Spanish monasticism, particularly the dorm room by Obra Sindical del Hogar y Arquitectura, and the foyer by Federico Correa and Alfonso Mil, with its bull’s horns. I also liked the varied textures and patterns in the interior by Oriol Bohigas and Jose Maria Martorelli. The names of these designers and architects may all be unfamiliar, but the work speaks across the decades, and there is no reason I can see why they should not be part of the current dialogue.

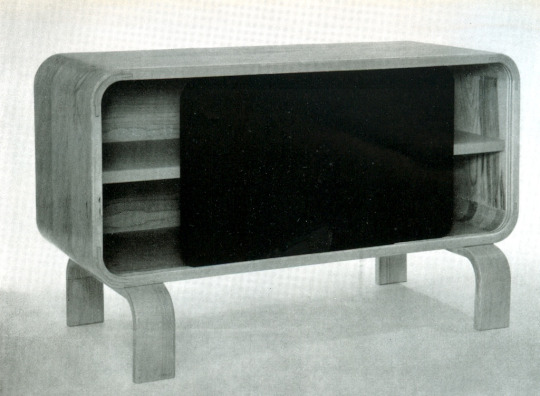

From top: steel and leather chair by Fernando Ramon; flexible coffee table by Antonio de Moragas; Constructivist chair by Brava, Lozano, and Pintado; chair by Miguel Fisac Spain; plywood chair by Jose Dodero; ribbed chair by Equipo 57; Cabinet by Salvador and Tomas Diaz Magro; interior by Obra Sindical del Hogar y Arquitectura; interior by Federico Correa and Alfonso Mila; interior by Oriol Bohigas and Jose Maria Martorelli.