Originally posted December 18, 2008 on interiordesign.net

Top photo courtesy of: http://rarevictorian.com/george-hunzinger-1869-patent-sidechair

That George Hunzinger (1835-98) is not a household name like Michael Thonet or even Charles Eames, owes as much to the vagaries of fashion as to any shortcomings on Hunzinger’s part. A German immigrant from a family of cabinet-makers, Hunzinger was a Victorian-era inventor (he held 21 patents) and designer whose commercially successful body of work embraced machine production methods and materials. Regarded by historians and critics as a proto-modernist, Hunzinger was the subject of a retrospective exhibition “The Furniture of George Hunzinger: Invention and Innovation in Nineteenth-Century America” held at the Brooklyn Museum in 1997. In a review of this exhibition, Roberta Smith of the New York Times lauded Hunzinger’s most innovative and forward-looking chairs for their transparency and structural rigor, and for offering an early glimmer of modernism’s emphasis on abstraction and visual austerity. The exhibition, she wrote, “showed furniture shedding its Victorian padding like a butterfly emerging from its chrysalis.”

Despite praise like this from a high priestess of design criticism, Hunzinger’s work continues to languish in the market–examples of his work sell for as little as a few hundred dollars on e-bay–and his name remains relatively obscure even in design circles. Surely, much of this is due to modernism’s aversion to things Victorian, and to Hunzinger’s own entrepreneurial savvy, which resulted in a large number of utterly conventional Hunzinger designs–clunky and overly-decorated, they are rightly consigned to the dustbin of history. Even many of Hunzinger’s progressive designs do not escape the trappings of historicism and revivalism, and so look to us more like caterpillars than butterflies. It takes a closer examination to detect the underlying modernity. Left are a handful of stripped-down designs that feature Hunzinger innovations such as cantilevered frames and wire-mesh seats and backs, along with machine-inspired, lathe-turned decorative elements. Spare and abstractly beautiful, these designs rise above Victorian meretriciousness and clutter like the aforementioned butterfly. I cannot explain why they are not as much a part of the modernist canon–and the modern design market–as Christopher Dresser’s metalwork, E.L. Godwin’s Japonesque sideboards, or Michael Thonet’s bentwood chairs.

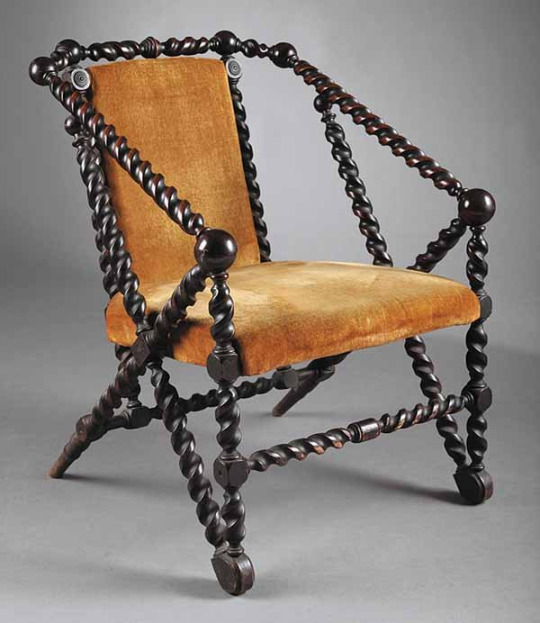

A look at a few actual Hunzinger pieces should be instructive. The chair with the spiral lathe-turned frame and caramel colored seat looks, at a glance, like a conventional Jacobean-revival design. A second look at the frame–a turn of the screw–reveals that the spiral elements also resemble a drill bit or machine part, and this reveals a deeper dialogue about the role of ornament in a machine age. More forward-looking is the suspended seat and back, which look–and float–like a mid 20th-century design. The armchair with the neo-classical pediment and Ottoman arches contains a mélange of motifs, per Victorian praxis, yet the whole is harmoniously and artfully balanced, and pulled together by the patented wire-mesh seat and back, which gives the work an architectural unity and bearing. This chair not only anticipates Carlo Bugatti’s historicist work of the 1920’s, but with its historical references and wire grid is curiously proto post-modernist, though without the irony or quotation marks.

It is fitting to end with a look at the two most stripped-down chair designs, which appear the most modern to our eyes. Both of these chairs have the wire-mesh seat Hunzinger innovated in the 1870’s. This feature in one stroke eliminated the clutter and heaviness of the spring-batting-and-draped fabric typical of Victorian upholstered furniture, and did so using materials and methods suitable to the machine. This experiment with wire mesh pre-figured the wire-mesh chair designs of Bertoia and Eames in 1951. Both chairs also have cantilevered seats and transparent structure. Both have reticulated turned elements that resemble bamboo, a Japanese inspiration. The chair with the asymmetrical back is particularly Japonesque, locating Hunzinger in a vanguard with Dresser, Godwin, and Frank Lloyd Wright in recognizing and incorporating this powerful modernist influence.