Originally posted June 10, 2010 on interiordesign.net

“The most important thing [in architecture] is not to construct well but to know how the majority of the folk live.” -Lina Bo Bardi, 1975

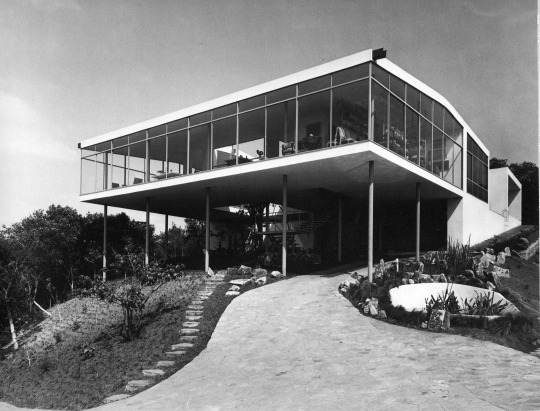

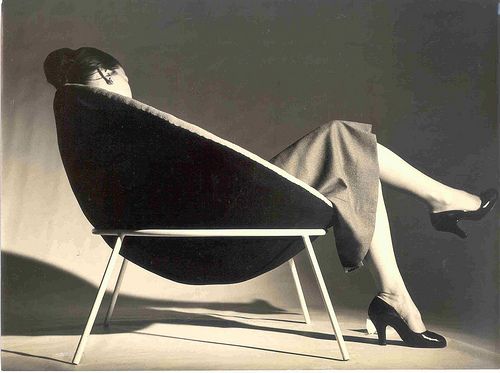

Lina Bo Bardi (1914-92), the Italian/Brazilian polymath, remains an under-appreciated modernist architect, designer, and thinker. The reasons for this surely include gender-as a woman, she was overshadowed by Niemeyer and Costa, and by Rodriguez and Tenreiro. Also, a lavishly illustrated treatise published in 1993 by the Instituto Lina Bo e P.M. Bardi is written in Portuguese (thanks to my half-Brazilian summer intern, Anna Levenshus, for her translations), and a perceptive article from 2002 is in the Harvard Design Magazine, neither of which sit on many American coffee tables. Of her architectural projects, The Glass House (1951) and the Sao Paolo Art Museum (1957-68) are perhaps known, as is the Bowl Chair (1951) among her designs. The rest is ripe for rediscovery and reevaluation.

It is tempting to see Bo Bardi as a sort of hybrid flower, transplanted from Italy to Brazil, where she blossomed in the unfettered and lush environment, trading an early Corbusier for a mature Frank Lloyd Wright as an avatar, shucking the encroaching formalism of the International Style for a direct and unencumbered engagement of local needs (both material and psychological), customs, topography, and materials. In short, as a proponent of the sort of dynamic and organic modern architecture advocated by Bruno Zevi, with whom she edited a journal in the mid 1940’s. Zevi, an Italian Lewis Mumford, opposed classicism, reductionism, or a priori thinking and embraced, a la FLW, an architecture style oriented toward space and the life taking place within that space. To Bo Bardi, the rain forest/wilderness held a promise of creative liberation: “Brazil is an unimaginable country, where everything is possible.” Bo Bardi’s thoughts about the Brazilian zeitgeist, quoted above, points in this direction.

The problem with this notion is that Bo Bardi was pretty much full-grown before she left for Brazil. She possessed a degree in architecture, was well-versed in Italian rationalism, influenced by early Corbusier, and by the design agenda of Gio Ponti, for whom she worked and edited. Tossing Zevi into the mix makes for a complex mix. On some level, Bo Bardi absorbed and internalized any number of conflicts within avant-garde modernism. Her career in Brazil probably represents a working through of these conflicts rather than any resolution of them-abandoning a priori thinking is easier said than done.

Five of the six images shown here illustrate this. The Glass House, built as her own residence in 1951, is obviously less William Wurster than Mies or Philip Johnson. The early photo of the house, sans flora, shows a sort of Farnsworth House on pilotes–a glass box plunked down on the edge of a rain forest. That Bo Bardi replanted and intended the rain forest to grow back around the house makes little difference-the photo has its own visual and historical reality. The second image, with the house hidden amidst the flora, casting ever-changing reflections, is closer to the Johnson Glass House of 1949, and more in the direction of the dynamic/explosive/regional, providing that the rainforest was allowed to grow back naturally and chaotically (as opposed to the planted, pruned, mowed, and over-determined landscape at the Johnson House). The overall impression is of an International Style goldfish bowl, a holding tank for acclimating to a new environment.

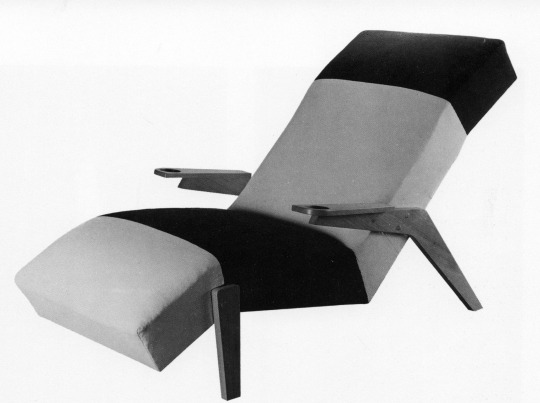

Similarly, the two furniture designs shown here, while very much of their moment synchronically, are less specific in terms of place. Either one could have been designed and produced in Italy-the chaise of 1948 is reminiscent of Ponti in its shape, the planes of the arms, and two-tone graphic character of the upholstery, while the Bowl chair of 1951-a rationalist hemisphere atop a circle and four lines-could have been done by Roberto Mango. Unless the bowl represents a coconut shell, there is little connection to Brazil. More connection is seen in the Casa Cyrell of 1958, with its thatched roof, local ceramic shard-laced cement walls outside, Santos inside, and profuse vegetation everywhere.

All this only suggests that Bo Bardi, like Corbusier, like Frank Lloyd Wright, was a complicated figure. Any reassessment of her career needs to apprehend this. Her story, as it continues to emerge, will shed light on a number of Big Themes in the history of design and architecture-gender, politics, philosophy, aesthetics, housing and so on.